It is said you should never assume, but living with a hop growing family I did just that and simply assumed that everyone, especially those connected with beer or brewing knew how hops had been and were dried now. So last month when 3 people, 2 brewers and one person who had been hand picking all his young life had all been equally surprised to learn that hops were once dried with coal and charcoal I had to re-evaluate my presumptions quick sticks.

Apologies to those who do know (please skip this next bit) but for those who don’t know or have never had cause to consider it, I will share what I have picked up from hearsay, practice and reading, and give a very brief account of what happens in an oast house. It is the basis of how A Bushel of Hops came about so is relevant.

In the High Weald wood is plentiful, hence the Romans found it convenient to build their iron furnaces in the area. On the family farm wood was cut in preparation for the charcoal burners to arrive during the summer. Their camp was a corrugated tin hut on wheels similar to a shepherds hut and they would live here while they prepared the charcoal on site ready for the hop picking in September, then move on until the following year. My husband and his mate as small boys can remember the charcoal burners well. The men would store their screw top quart bottles of Fremlin’s beer, each bottle in a sock placed carefully in the stream next to their camp. The charcoal stacks were built but as boys my husband and his mate never actually saw these stacks lit. The burners were secretive and always found the boys a job away at the crucial time, so the actual lighting always remained a mystery. The coal came in from Wales to the local railway station where it would be collected by horse and cart.

Coal was used in the kilns for the main grunt of the hop drying time with the charcoal added towards the end of each drying to raise the temperature to ‘finish’ each load of hops. The whole length of this drying would take on average 10 hours – 12 hours to complete. The other difference was that hops were not loaded onto the kilns very deeply, only 6 inches maximum. Todays modern kilns can be loaded up to 3 feet in depth, but back then they were relying on natural draught to keep the air flowing up through the bed of hops and out via the cowl. The cowl turns in the wind, the purpose of which is to cause a slight vacuum as it keeps its back to the wind. In effect the roundel is a giant chimney. Air is important to any load when drying, if hops sit on the kiln, warm and with no air passing through them, then they will just ‘stew’, begin to compost and spoil. The hop dryers job is skilled but also in part an art.

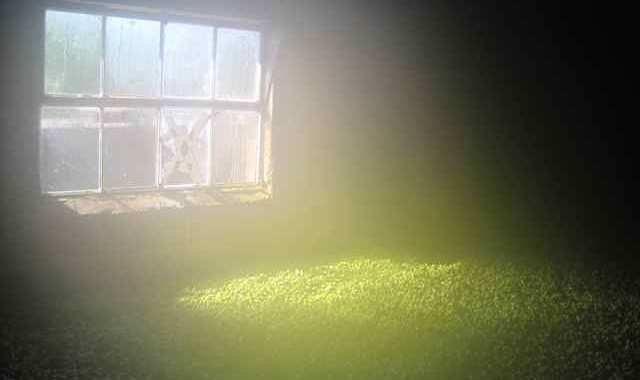

Reek (moisture) coming off a load of hops. a lot of water vapour has to be removed on a large kiln load of hops

Reek (moisture) coming off a load of hops. a lot of water vapour has to be removed on a large kiln load of hops

As hop acreage on each farm increased more throughput, therefore more drying capacity in each kiln was required, so in order to load a bit deeper they introduced fans above the drying hops which sucked air. It is the air passing through in balance to the depth of hops that is critical. These fans were often run by a Lister type engine on the ground, this allowed the hops to be loaded a little more deeply and was happening around the WW2. On the family farm when the fans in the oast house roundels had to be serviced the men remembered the Battle of Britain taking place overhead. I am sure that produced a few scary moments with them wishing they are back on the ground!

The next stage, as growers needed even more efficiency to remain viable, was for high pressure blowing fans, as opposed to sucking fans, to be used. Instead of above the drying floor, these were installed underneath the bed of hops. These oil fired drying units were and still are used which force huge quantities of air up through the crop and the temperature can be accurately adjusted. However, Pentland Crown potatoes can no longer be baked in the ashes while you wait for the hops to dry.

Reek looks like smoke – here coming off a modern kiln with a larger load of hops drying

Reek looks like smoke – here coming off a modern kiln with a larger load of hops drying

So this was the start point where A Bushel of Hops was born – It was never planned, it just sort of seeded itself as an idea and grew from there along with the few heritage hop varieties I started out with just for my own interest. As a small hop grower I would need to find a niche and it had to tick several important boxes. It had to be separate and fingers crossed eventually viable, I can never compete with the larger growers, nor do I wish to. I also knew I wanted to keep the business small and personal, grow a selection of British hop varieties for the home brewer, this was something I simply enjoy doing. The other thing that appealed strongly was that I knew I genuinely wanted to keep these hop drying skills and knowledge alive within a business, not solely as the preserve of a museum.

The up shot then …. well knitting would have been easier and it would have been far more sensible and certainly less stressful at times. But hop growing comes with a warning – it is addictive. And is it immensely exciting? yes definitely, is it unpredictable, never once boring and endlessly fascinating with loads more to learn?… of course without any doubt.

As Mark Tranter of Burning Sky Brewery succinctly summed it up saying “sometimes if you have an itch, you just have to scratch it”!